John Betts - Fine Minerals > Home Page> Educational Articles > Minerals of Anthony's Nose, New York |

Anthony’s Nose, New York A Review of Three Mineral Localities

- Page 4

This web page is provided as a resource to mineral

collectors.

Contact the property owner before entering the property to obtain written

permission to collect minerals.

John Betts does not own this property and he cannot

grant permission to enter the site.

Mineralogy

The following summary is derived from observation during the summer of 1997 and from Peter Zodac’s (1933) exhaustive article on the mine.

Albite in massive greenish to gray-green to brown in association with black hornblende. Generally, as with most minerals from Philips Mine, the albite is heavily stained with limonite, penetrating the mineral to the extent that identity is obscured. The green variety of albite is attractive as a mineral specimen and is best found at the lowest dump at the Philips Mine.

Actinolite occurs as gray-green, poorly crystallized masses in altered rock or with magnetite. Also present as a constituent of the albite porphyry at the mouth of the middle tunnel as small masses and grains.

Amphibole var. Amianthus (Brucite ?) is found at the Philips Mine in small fibers with asbestos in minute veins in hornblende.

Amphibole var. Asbestos is found in several specimens as small tufts in crevices and minute veins in hornblende.

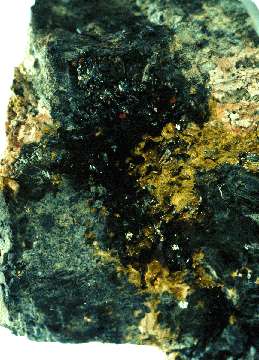

Figure 22 - Apatite in iron-stained pyrrhotite collected

1997. The crystal is doubly terminated and is a ½ inch long.

Figure 22 - Apatite in iron-stained pyrrhotite collected

1997. The crystal is doubly terminated and is a ½ inch long.

Apatite is the most collectable mineral at Philips Mine because they occur as translucent to opaque brown, yellow or green crystals up to one and a half inches long. They are best found within masses of pyrrhotite and are closely associated with pyrite often and the contact of these two sulfides. There are reports of crystals up to two inches long and another one and a half inches diameter (Zodac, 1933), however the larger crystals are often poorly crystallized and difficult to find unbroken. The collector can expect to find lustrous, doubly terminated crystals up to three quarter of an inch long without much difficulty. Reportedly the best crystals are found in pyrrhotite nodules that apparently were the nucleus around which the pyrrhotite formed. These are said to be found abundantly east of the upper tunnel, though the author has not found any such nodules during recent visits to the Philips Mine.

Aragonite occurs as encrustations of poor quality coating various minerals.

Arsenopyrite from the Philips mine is listed in the collection of the New York State Museum in Albany.

Barite was present in one specimen at Philips Mine found as amygdaloidal form in altered rock. This nodule contained minute grains of pyrite and was coated with a thin blue crust, apparently a copper sulfate.

Biotite is common as a primary constituent of the Canada Hill granite where a crude orientation of the biotite gives the granite a layered, foliated appearance. At the Philips Mine with it is associated with hornblende, magnetite, labradorite and apatite.

Calcite is abundant but not as collectable minerals specimens. Occurs as tabular, colorless masses in granite and as gray crystallized clusters on augite.

Chalcopyrite occurs at Philips Mine as massive, often brightly colored (peacock ore) associated with black hornblende.

Epidote is common in lenticular pods throughout the Canada Hill granite. It is found at the Philips Mine at westernmost prospect pits in the fault plane of the granite. Also visible as small yellow grains in quartz at the prospect pits.

Gypsum, var. Selenite is common at Philips Mine as micro crystal coatings in cavities and on other minerals. It is likely that these crystals formed since mining began as it is visible in the tunnels and on heavily decayed minerals on the dump.

Hematite as botryoidal formations resembling psilomelane occurs at the Philips Mine and as red coatings of magnetite. Slag-like specimens can be found at lower dumps and in the soil south of the mine road. These may be the by-product of an on-site smelting furnace, though there is little evidence that smelting took place at the mine.

Hornblende is common at Philips Mine as large masses and coarse crystalline specimens up to two feet long (Klemic et al., 1959). Associated with green albite on the lower dump of Philips pyrrhotite mine. Also occurs with augite, magnetite, pyrite, apatite and quartz. The best specimens of this mineral occur as small green crystals on magnetite and augite or as slender black crystals in small cavities in the hornblende masses.

Langite, possibly the first occurrence of this in America was reported at the Philips Mine by Zodac (1933):

The best "find" at the mine is langite, a hydrous copper sulphate, which was found September 9th (1932), by Mr. Charles Travis. It occurs in minute, well-crystallized, bluish-green prisms in altered rock, and is associated with at least one other copper mineral, and possibly two, whose identifications have not yet been determined. This is believed to be the first occurrence of the mineral in America, and possibly the second in the world, as it has heretofore been listed from only one locality, Cornwall, England.

Magnetite was once the principal ore at Philips Mine when the mine was worked in the early years for iron ore. It is found commonly on the dumps, notably at the northwest of middle dump. Magnetite is associated with hornblende and augite and can be found in large masses on the dumps. No crystals have been reported from the mine.

Oligoclase occurs as massive specimens and is a common mineral in the surrounding country rock.

Opal, var. Hyalite was found in a single specimen from a prospect in the fault plane of the granite. The specimen was small but showed botryoidal form. (Zodac, 1933)

Orthoclase is common as part of the Canada Hill granite and as part of the dark hornblende gneiss visible at the mouths of the tunnels.

Pentlandite from the Philips mine is listed in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Pyrite is widespread on the dumps at the Philips Mine as cubic masses within the pyrrhotite and recognizable by the bright yellow color. It is associated with magnetite, hornblende and albite.

Pyroxene, var. Augite is common as large masses. A five and a half pound specimen was found at the Philips Mine that measured 5 x 4 x 2.5 inches on the lower dump (Zodac, 1933). Augite is associated with magnetite, hornblende and milky quartz and is common as an alteration of the older hornblende in the pegmatites..

Pyrrhotite is the most common mineral on the dumps at the Philips Mine. It is likely that this is due to the later workings of the mine for sulfur for the production of sulfuric acid that focused on sulfur-rich ore. It occurs as nodules and as massive ore. The nodular variety invariably has a euhedral apatite crystal at its core. Due to the long exposure to weather of the ore on the dumps, the pyrrhotite has been heavily stained with alteration minerals of iron. To date the author has not successfully found a way of cleaning this iron staining, making collecting the pyrrhotite fruitless at this time. However since the nodules contain the apatite crystals they are worth looking for.

Quartz is present as constituent of the gangue rock commonly showing crystal form however quality free crystals have not been seen on the dumps recently.

Titanite in well crystallized specimen at Philips Mine.

Uraninite was found as grains and crystals 1 to 25 mm long associated with magnetite and hornblende in the pegmatite bodies near the mine. The uraninite was dated by isotopic dating to 920 million years old (Klemic et al., 1959). Uraninite is found in greater concentrations in the prospect pits southwest of the main shaft along the mine road.

Alteration minerals from the iron ores: limonite, goethite, copiapite, melanterite, lepidocrocite. (Zodac, 1933)

Current Status and Access

Presently the original mine road from the northeast is closed because it crosses through private property. It is posted No Trespassing and collectors are advised to stay clear of these houses. (As of the summer of 1997, several of these properties, with nice summer homes, were for sale.)

The Appalachian Trail passes within 200 yards of the lower mine dumps , in the section south of South Mountain Pass Road. From the east end of Bear Mountain Bridge, drive north along Route 9D to South Mountain Pass Road, turn right and proceed approximately .7 mile to a small turn out on the right. This is where the Appalachian Trail from the south meets the road. Park off the road near the trail. Hike south along the Appalachian Trail (white trail markers). Continue 100 feet past the metal vehicle gate, and then bushwhack uphill to the left through the trees for 300 feet. If you encounter a small stream, stay to it’s right and this will lead you to the lowest mine dump. From here the mine areas are clearly visible through the woods, as no vegetation can grow on the iron oxide saturated ground. The lack of vegetation can be seen as you are bushwhacking uphill as an area of no tree cover - keep heading towards that opening and you will encounter the mine within 100 yards.

It is possible to find the mines by continuing on the Appalachian Trail further to a blue blazed trail the goes uphill to the left. Old topographic maps show the Appalachian Trail went this way to a spring on Mine Hill, then passed though the mine workings. However this route has not been well mapped recently and it is safer to follow the route suggested.

Most minerals are encrusted with iron oxide coating making collecting and field identification difficult. Larger rocks must be broken open to expose fresh surfaces and cavities for collectable mineral specimens. Pyrrhotite ore is easily recognized on the dump by the iron oxide (limonite/goethite) coating. The product of the decay of the pyrrhotite drips around to the bottom of each nodule forming a coating and conglomerating with nearby rocks and debris.

Apatite is associated with pyrrhotite nodules that contain the bright yellow pyrite, often near the contact of the two minerals. Apatite varies from brown to green to yellow. Most of the larger crystals are opaque while the smaller crystals (<2mm) can be very translucent.

Cool breeze strongly emanates from the upper tunnel, caused by air entering the large shaft being cooled by the surrounding rock creating downward flow. The lower tunnel is partly caved at the entrance and water filled, preventing air from escaping at that level.

There are several known prospect pits scattered southeast, south and southwest of the main shaft. The furthest of which is 500 yards southwest. The known prospects are mapped in Figures 15 and 16. These prospects have also been a source of minerals for collectors.

Route 6 Road Cut, Cortlandt, Westchester County, New York

This location is the only modern site included in this article. In March, 1991 the New York State Department of Transportation widened the road cut opposite the scenic overlook on Route 6, three quarters of a mile southeast of the Bear Mountain Bridge. The excavated rock was dumped down the embankment northeast of the parking area (Zabriskie, 1992).

Driving from the eastern end of Bear Mountain Bridge, follow Route 6 three quarters of a mile southeast of the bridge to the scenic overlook. Park at the overlook. Collecting at this site is best in the excavated rock that was dumped down the hill across Route 6 from the road cut northeast of the parking area. After parking, hike east along Route 6 for 50 yards then proceed downhill carefully, as the dumped rock can be unstable.

At left, view from scenic overlook parking area east along Route 6. The collecting are is downhill to the right. At right, view of the rock dumped during the 1991 widening of the road cut.

This location was the site of a New York Mineralogical Club field trip in

1994 during which many different mineral species were collected. At the time

the dumped rock was fairly fresh as was the road cut that was widened. Upon

inspection in 1997 the road cut was found to be extensively overgrown with

high weeds. Since the actual road cut itself has never been the primary focus

of collectors, this situation is unimportant. The dumped rock in the collecting

area also shows overgrowth but is still accessible to collectors. Recently,

several additional mineral new mineral occurences have been identified from

this location by field collectors.

Mineralogy

Following is a summary of the known minerals found at the Route 6 road cut:

Apatite - collected by D.O.T. and New York State Museum personnel during the 1991 excavation.

Chabazite - orange rhombohedral crystals, confirmed by X-ray identification, were collected by D.O.T. and New York State Museum personnel during the 1991 excavation.

Chondrodite - scarce, unverified.

Clinochlore - common as crystals in cavities associated with epidote.

At right - Small pocket of lustrous epidote crystals with clinochlore collected in 1994.

Epidote - both massive and crystalline forming bright green micro crystals and in pockets associated with clinochlore. This is the primary mineral of interest to collectors at the Route 6 road cut.

Feldspar - in a cuttable grade that could be called moonstone.

Gahnite - as crystalline specimens were reported by D.O.T personnel during the blasting, though positive identification has not been made to date.

Hematite - many bladed crystals up to ½ inch found on one specimen.

Hornblende - as crystals in pockets and massive crystals in the surrounding rock.

Magnetite - scarce.

Heulandite - collected by D.O.T. and New York State Museum personnel during the 1991 excavation.

|

Above left - Radiating spray of natrolite crystal in zeolite cavity. Above right - Zeolite cavity of thin natrolite crystals with stilbite overgrowth making them look thicker in appearance. Collected 1994.

Natrolite - as long acicular crystals in cavities up to two inches long. Often coated with flesh colored stilbite completely obscuring the natrolite except where crystals have broken. This may turn out to be mesolite or scolecite as testing has not been completed.

Pyrite - widely scattered through the dump especially to the northeastern end, furthest from the parking area. Pyrite specimens are easily found as the surface is heavily rust stained and the heavy weight are sure indicators. Upon breaking open these specimens the cubic crystal structure can often be identified.

Stilbite - as micro crystal coatings upon natrolite crystal giving the appearance of thick, fuzzy acicular crystals. Where these have been broken the square cross section of natrolite is distinctly visible. Stilbite also found as radiating crystals in narrow seams in the surrounding rock.

Titanite - massive gray and rarely as crystals, confirmed by X-ray identification, were collected by D.O.T. and New York State Museum personnel during the 1991 excavation.

Vesuvianite - recently reported by Zabriskie (1995) however positive identification has not been made at this point in time.

Since this is the youngest site on Anthony’s Nose it has received much less scrutiny by collectors and professionals. Therefore not much has been written about the location. The relative freshness of the rock on the dump makes this site better for collectors compared to the 100 year old rock available at the other two locations. The author suspects that as this site receives more attention that additional minerals will be added to the list above.

Conclusion

The author hopes that by mapping mineral locations and clarifying the mineral occurrences at each site, that collectors will once again turn their attention to these sites for field collecting. The sites in this paper, that are up to 150 years since old, are extreme examples of lost sites that still offer collectors potential for good specimens.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank everyone that assisted in the preparation of this paper. Most importantly the author acknowledges Steve Nightingale for permitting me to reproduce the specimen in his collection and assistance in researching the mineral literature; Alex Gates of Rutgers University, Newark, NJ for reviewing the geology; Dr. William M. Kelly and Mike Hawkins of the New York State Museum. A special thanks is extended to Mike Hawkins for sharing first-hand information, assistance in researching the localities, obtaining illustrations and reviewing this paper for accuracy.

References

Anonymous (1991) 50 Mile Radius Map from Columbus Circle, New York City. Hagstrom Map Company, Maspeth, NY.

Anonymous (1997) East Hudson Trails, Map 1, Hudson Highlands State Park. New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, New York, NY.

Anonymous (1997) East Hudson Trails, Map 3, Clarence Fahnestock State Park. New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, New York, NY.

Beck, Lewis C. (1842) Mineralogy of New York. Albany, New York

___________ (1849) Second Annual Report of the New York State Cabinet of Natural History, Comprising Notices and Additions Which Have Been Made Since 1842. Albany, N.Y.

___________ (1850) Third Annual Report of the New York State Cabinet of Natural History, Comprising Notices and Additions Which Have Been Made Since 1842. Albany, N.Y.

Berkey, Charles P. (1911) Geology of the New York City (Catskill) Aqueduct. New York State Museum Bulletin 146, Albany, NY.

_______________ (1933) New York City and Vicinity. International Geologic Conference, Guidebook 9: New York Excursions, New York, N.Y.

_______________ and Rice, Marion (1921) Geology of the West Point Quadrangle, NY. New York State Museum, Bulletin 225,226, Albany, NY.

Dana, J. D. (1892) A System of Mineralogy. Sixth edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, p.270.

Egleston, T. (1892) A Catalogue of Minerals and Pseudonyms. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Heinrich (1958) Mineralogy and Geology of Radioactive Raw Materials. McGraw Hill, New York, N.Y.

Howell, William T. (1934) The Hudson Highlands, Volume II. Reprinted 1982, Walking News, New York, N.Y.

Jensen, David E. (1978) Minerals of New York State. Geneva, NY.

Kemp, J. F. (1894) Pyrrhotite Deposits at Anthony’s Nose on the Hudson, N.Y. American Institute, Min. Eng. Transactions, p. 620

Klemic, H., Eric, J. H., McNitt, J. R., and McKeown, F.A. (1959) Uranium in Phillips Mine-Camp Smith Area, Putnam and Westchester Counties, New York. U.S.G.S. Bulletin 1074-E, Washington, D.C.

Loveman, Michael Heilprin (1911) Geology of the Phillips Pyrites Mine Near Peekskill, New York. Economic Geology, Vol. VI, No. 3, p. 235.

Manchester, James G. (1931) The Minerals of New York City and Its Environs. New York Mineralogical Club, Bulletin Volume 3, No. 1, New York, NY.

Mather, William W. (1843) Geology of New York, Part I, Comprising Geology of the First Geological District, Albany, NY.

Newland, D. H. and Hartnagel, C. A. (1928) The Mining and Quarry Industries of New York for 1925 and 1926. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

Robinson, S. (1825) A Catalogue of American Minerals, with their Localities. Cummings, Hilliard, & Co., Boston, p.115.

Schuberth, Christopher J. (1968) Geology of New York City and Environs. Natural History Press

Tervo, William A. (1967) The Rock Hounds Guide to New York State. New York, NY.

Zabriskie, Dan and Zabriskie, Carol (1990, 1995) Rockhounding in Eastern New York State and Nearby New England. Many Facets, Albany, N.Y.

Zodac, Peter (1933) The Anthony’s Nose Pyrrhotite Mine. Rocks & Minerals, Volume 8 No. 2, p. 61-76.

____________(1939) A Remarkable Melanterite. Rocks & Minerals, Volume 14 No. 2, p. 253.

This article was first published in the Winter, 1997 issue of Matrix magazine, a journal of the history of minerals. Subscriptions are $24.00 per year. For more information write Jay Lininger, Matrix Publishing Co., P.O. Box 129, Dillsburg, PA 17019-0129. Phone 717-432-7109.

© John H. Betts - All Rights Reserved

This locality information is for reference purposes only. You should never

attempt to visit any mineral localities listed on this site without written

permission of the land owner and/or mineral rights owner and that you follow

all safety precautions necessary to protect yourself and the property.

Unfortunately, the status of mineral collecting sites change often. Inclusion

in this site does not give an individual the right to trespass. ALWAYS ASK

PERMISSION prior to entering a collecting location. ALWAYS RESPECT THE PROPERTY

OWNER, you are his guest. Never enter a property posted no trespassing. When

in doubt, do not enter the property.

John Betts - Fine Minerals Home Page

Please support our sponsor

© John H. Betts - All Rights Reserved